by Mark Piggott

Honestly, I lost count of the reincarnations I have gone through. I remember one life to the next, memories stacked upon memories, and it has been that way since the dawn of time. Centuries pass by so quickly, sometimes as swiftly as my many lives.

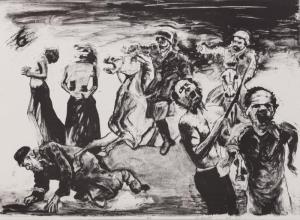

It was hard to forget the pain and suffering I endured, often wondering what Hell was like. I realized it was here and now in whichever life I was currently living. Never reaching the end of the tunnel of light, I always found myself instantly reborn in a different lifetime. I always lived a rather unremarkable life before experiencing a seemingly horrible death.

It was a terrible thing being a baby with so many memories floating around in my tiny little head. I constantly plagued my mothers with terrifying cries, night and day. No lullaby, swaddling, or taste of mother’s milk would satiate my pain. I never meant to torment them, but I could not help it. I prayed that once they found out who I was in the afterlife, they would find it in their hearts to forgive me for causing their sleepless nights and constant suffering.

My fathers, on the other hand, were not as forgiving. They were all harsh men, stern in their discipline, especially toward me. Crying was a sign of weakness, and they all thought I was weak and needed to be toughened up. Beatings became a regular part of my daily life, just more of the Hell I lived through within these multiple reincarnations.

I often wondered if God had a sense of irony when he subjected me to this torture. I could not shake these demons as I moved from one life to the next. Nothing seemed to change my destiny, no matter what I did during these incarnations. I have lived the simple life of a farmer, a scribe, a priest, and a fisherman, but the evils of my past still haunted me to my death. I tried being a soldier and a gladiator, anything to defend myself from the cold grip of death, but nothing worked. I was a cursed soul destined to wander this world forever.

I now find myself in 1939 in the occupied territory of Nazi Germany. I am only eight years old, so I do not understand the politics of it all. My father called them fascists and told me how much they hated Jews, calling us sub-human and a blight on humanity. That confused me because Yeshiva school taught us that we were God’s Chosen People.

In this new life of mine, my family was from the Iberian Peninsula, Sephardic Jews from Spain. We were visiting non-Jewish relatives in Hungary when the Nazis invaded. Then the edict came down from the Nazi commander—all Jews were to report for relocation. Papa tried to get us the proper papers from the Spanish Embassy to return home, but their powers were limited by the Nazis, especially when it came to Jews. Mama wanted us to go into hiding like other Jews, but Uncle Ambros feared that would endanger his family.

They argued for hours, nonstop at times. I could not bear to listen to it anymore and hid in the wardrobe, covering my ears to drown out the sorrow and pain, but nothing mattered. In the end, we had no choice. The Nazis finally took me and my family away while the police arrested Uncle Ambros for harboring Jews. Nothing that anyone said or did could change our fate. My destiny struck me and those around me again.

Papa and I were separated from Mama and Bubbeleh—my little sister, Ariella. We cried and clutched at each other as they pulled us apart. I desperately clung to them, longing to keep a tight grasp on their hands again. The soldiers shoved us into railroad cars, packed tighter than a can of sardines. There must have been a hundred of us in this tiny railcar. It was cold and smelled like a toilet. There were Jews, some Romani Gypsies, and people my papa called political prisoners. Some were younger than me, and others were older than my grandfather in Spain. They were from various professions—musicians, teachers, jewelers, and scholars from Hungary, Austria, and other countries. They seemed perfectly harmless, not a threat to anyone. I could never understand why the Nazis feared and hated us so much.

We huddled close together for warmth which was easy with everyone shoved into this tiny box. Even still, nothing could fend off the freezing temperatures filtering in from the outside through the little windows and thin wood constructing this railroad car. On top of that, I had nothing to eat for days. Papa gave me some snow and ice from outside the window to satiate my thirst, but it did nothing for my hunger. My mouth watered for one more taste of my mother’s vegetable soup with a piece of crusty bread. It was a simple meal yet full of flavor, and my stomach growled for one more spoonful.

The one thing that was readily present in that rail car was fear. It had a fetid taste in the air during the entire trip. I had sensed enough of it in my many lifetimes. I recognized the intensity of the whispers being passed around like gossiping women. They spoke about work camps and death camps, burn pits, firing squads, and even rumors of gas chambers. I did not know what it all meant, but the fear grew with every mile traveled on the tracks.

There was also the smell of death, something unmistakable. The days traveled were not easy for some of the older passengers. They dropped like flies in buttermilk, more and more every day with every mile of railroad track traversed. These poor people could not survive such a strenuous journey, but that was what our captors had hoped for. My father shielded my eyes and told me not to look while the men from our car pulled the dead bodies from the train and discarded them like moldy bread.

At times like this, I noticed how the soldiers would yell derogatory names to humiliate us and question our humanity. Ratte, Schwein, Mongoloid, and Jude were just a few of the names thrown our way. Their hatred was personified in the words they spewed, but as my father taught me, “words of hate float effortlessly on the wind, only to fall on deaf ears.”

Besides the disposal of the dead, the train only stopped for coal and water for the locomotive and food, but that pleasure was only for the guards. We were left in the bitter chill to suffer while our Nazi captives went inside to rest next to a warm stove with hot food and beverages to fend off the chill of winter. The further we traveled, the colder it got. One of the other men said we were heading north, through Germany and into Poland. I wished for a glimpse of the countryside, but the windows were too high for a little boy like me.

I had to wait to see the light of day until the train reached its final destination. When the doors to the car opened, a biting freeze rushed in from outside. I thought the ride in the train car was cold, but the icy wind whipped through all of us. I felt frosty before—hiking in the Pyrenees with my cousins—but that was nothing like this. I could feel the chill in my very soul. I longed for the sun, but it remained hidden behind the clouds as snow fell. Everyone rushed for the door to put some circulation in their legs and start moving briskly for some semblance of warmth.

We were greeted by emaciated prisoners dressed in black and white striped clothing. They appeared undernourished, as if they had not eaten in months. The prisoners looked away from us as they helped the captives off the train. It was as if they knew our fate was already sealed. They did not want to look us in the eye for fear that their tears would give them away, but as far as I could see, they dried up a long time ago.

A man reached for me, and I saw a strange marking on his arm. It was something called a tattoo. I remember the sailors visiting our home in Spain with these tattoos, but they were usually mermaids, anchors, flags, and ships. This one was a series of letters and numbers. Papa and another gentleman in our train car discussed the markings with complete repulsion. It was just more “Nazi efficiency” in turning everyday people into notes on a ledger.

The guards lined the tracks with barking German Shepherd dogs being held back by leashes. Their masters kept a tight grip on the leather strap, waiting for someone to step out of line and let the dogs tear into them. They snarled their teeth at us like their masters. Other soldiers used whips to keep everyone in line. We were all compliant with every order because no one wanted to be whipped, especially me. I remember the sting of leather when my Uncle Ambros used a strap on me when I accidentally spilled his wine. That was something I did not wish to experience ever again.

A voice came over a loudspeaker, ordering all able-bodied men to move to the front of the train. They were then instructed to walk the fifteen miles to the camp while the women, children, and elderly were crammed into trucks. This was more division by the Nazis; we all knew it. Once again, they were separating the strong from the weak.

Like my mother and sister in Hungary, I was ripped out of my father’s arms as he was forced to the front of the line to walk to the camp. I was left in the care of an alte—an elderly man that befriended my father. He took my hand and smiled at me through his long, white beard. Even through his stained, yellow teeth, I felt slightly comforted when he assured my father he would take care of me.

While the men marched the slow and steady walk down the snow-covered road toward Auschwitz, we filed into the trucks for the long haul. The skinny prisoners did their best to help us into the truck bed. When everyone was loaded, they climbed in and sat beside us.

One man stared at me with intense curiosity, his eyes burning into my soul. I did not know him, but he seemed very interested in me. “What’s your name, my little man?” he asked me politely, something I would not expect of this place. I whispered it softly until the prisoner held his hand to his ear. I spoke up a little louder this time.

“Yaffa, Yaffa ben Canaan.”

“I mean your real name. The name you have been known since God cast Adam and Eve out of the garden.” I could not believe what I was hearing. He knew about me and the thousands of lives I lived. Was he a messenger of heaven or a demon sent to torment me?

“Cain. My name is Cain.” My name repulsed most people—the first murderer, the man who killed his brother. I have suffered for centuries, paying for my crime. No matter what I said or did, people grimaced at the sound of my name, but not this man. He smiled upon hearing my name, but I did not know if that was good or bad.

“Don’t be afraid, little one. God came to me in a dream with a message for you. He told me to tell you that your time in our world was ending. Your penance is nearly complete.”

“Nearly? What do you mean nearly?”

“The Nazis are flooding Hell by the millions. Their hateful and fascist filth fills the depths of purgatory, but they need someone to teach them the errors of their ways. God is ending your suffering on Earth so you may place it onto them.”

“I would not wish my life on anyone, not even Nazis scum who killed my family and friends!” I took my anger toward God out on this pitiful man before quietly backing down and looking away.

“The Torah teaches us that because humans have been given free will, they are responsible for their actions. If they commit a wrong action, they must seek forgiveness. Forgiveness can only be accepted by the victim.”

Hearing the teachings of the Torah from this pathetic man seemed out of place. “Are you a Rabbi?”

“I was, but I cannot lead my people anymore, not like this. Now, I can only follow the will of God. You will be the Nazis’ only victim in Hell because you, a murderer, can enter that domain. They will look to you for forgiveness, but you will judge them instead.”

“But why me? Haven’t I done enough penance in the thousands of lifetimes spent suffering?”

“And why do you think you suffered? You have faced the pain of humanity from one life to the next. You know what lies within the human heart through all you have survived. The time has come for you to put those experiences to the test.”

I listened to him and realized I had to follow God’s will. “I have no choice in the matter, do I?”

“No, my son, you don’t. But be at ease,” he said, touching my shoulder. “Your parents and sister from this life will wait for you in paradise. They are all waiting for you.”

“All of them? All of those families whom I tormented just by being born to them. Do you mean even Adam and Eve?” He nodded and smiled before his grin disappeared as the truck passed through the gate. Across the iron gate were inscribed the words “Arbeit Macht Frei” as plain as day. My German was a little rusty, so I did not understand what that meant.

“What do those words mean?”

“It means ’work sets you free,’ but that’s all a lie,” he said calmly. “Your fate was decided the moment you got on that train.”

“No, my fate was decided the day I killed my brother,” I replied, so matter of fact. “I will do as my God commands. I pray this ends my pitiful existence.”

“You don’t get it, do you, my son? Your name may mean murder, but your life has taught humanity a valuable lesson. We can learn from your example . . . murder and suffer the same fate as all murderers. You have suffered so that sinners around the world will learn the lesson of Cain and Abel.”

“Do you think he has forgiven me? My brother, Abel?” The rabbi did not answer when the truck came to a sudden stop. They were parked next to a stone structure that resembled an enclosed shower. I thought that because others were already disrobing, outside in the snow and cold, before entering the building. It seemed odd to do it out here in the freezing weather, but the Nazis were not one to provide for the convenience of their prisoners.

“Why don’t you ask him yourself when you see him again?” As the back of the truck dropped, the rabbi got down and reached out for me. “God go with you, Yaffa ben Canaan. May you find peace at last.”

THE END